Evidence-Based Sports Supplements for Elite Athletes: A Decision Framework for Performance and Safety

Posted In: Combat Sports, Individual Sports, Sports Nutrition, Team Sports

Introduction

In elite sport, marginal gains matter. When performance outcomes are decided by fractions of a second, athletes are understandably motivated to explore any legal strategy that may enhance performance. However, while supplement use is widespread among professional and Olympic-level athletes, scientific evidence supporting most products remains limited, and the risks—particularly under strict anti-doping liability—are substantial (Maughan et al., 2018).

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) emphasizes that supplements should never compensate for poor training, inadequate nutrition, or insufficient recovery. Supplementation should only be considered after comprehensive nutrition assessment and when a clear health or performance rationale exists (Maughan et al., 2018).

This article provides a structured, evidence-based decision framework aligned with IOC guidance, identifying the small group of supplements with credible performance support.

Key principle: In high-performance sport, supplements are a risk-management decision as much as a performance decision. Evidence, safety, event relevance, and quality assurance must all align before use.

The Supplement Decision Framework

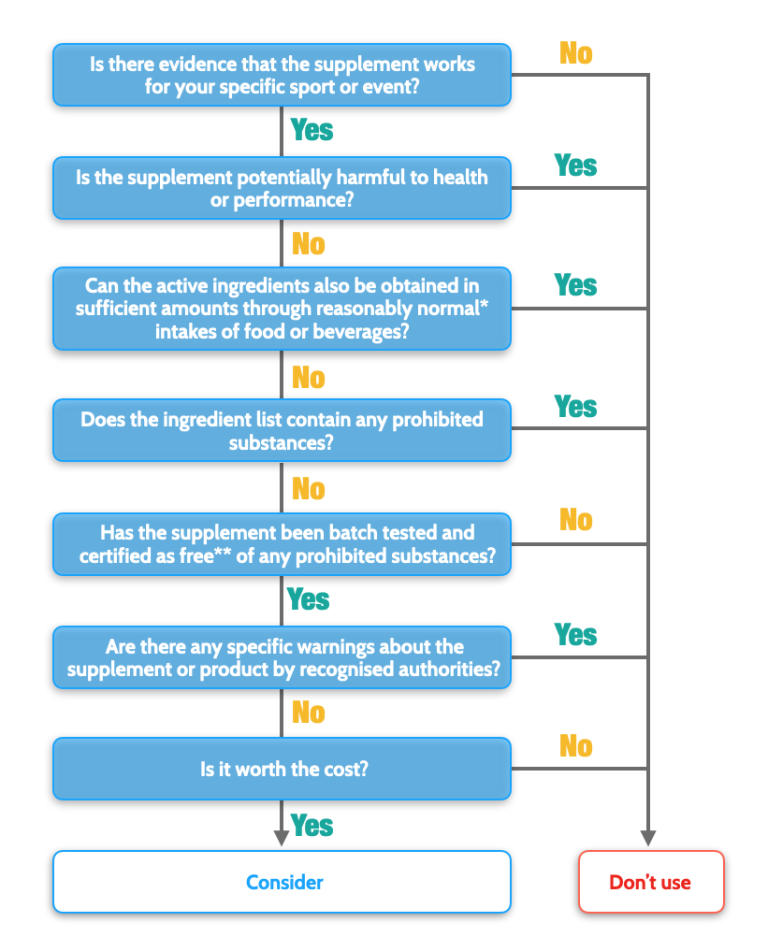

The IOC decision chart offers a practical sequence of questions that every athlete should answer before using any supplement. A single “no” at any stage should halt the process.

Figure 1. Supplement decision chart. Adapted from Jeukendrup & Gleeson (2018)

Step 1: Is the Athlete Ready for Supplement Use?

Athlete readiness includes training age, competition level, nutritional adequacy, recovery practices, and performance goals. For developing or junior athletes, supplement use is generally discouraged unless a clinically confirmed deficiency exists (Maughan et al., 2018). If training quality, energy intake, or sleep are inconsistent, supplementation is unlikely to provide meaningful benefit.

Step 2: Is There Scientific Evidence?

Evaluate quality of evidence, not popularity or anecdote. High-quality evidence includes randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and consistent findings in trained athletic populations. Most supplements fail at this stage—the IOC recognizes only a limited number with reproducible performance effects (Maughan et al., 2018).

Step 3: Is the Supplement Effective for My Event?

Even evidence-based supplements are event-specific. A product that improves repeated sprint ability may be irrelevant for endurance events, and vice versa. Elite athletes must evaluate exercise duration and intensity, energy system demands, competition format, and tactical constraints. Failure to match supplement use to the event model is one of the most common errors in elite sport practice.

Step 4: Is It Safe to Use?

Safety includes known side effects, interactions with medications or other supplements, tolerance during competition stress, and dose-response characteristics. Some supplements with theoretical benefits may produce gastrointestinal distress, cardiovascular symptoms, or impaired sleep, negating any potential performance gain (Burke, 2017).

Step 5: Does It Come from a Reliable Source?

Under strict liability, athletes are responsible for everything they ingest. Multiple investigations have demonstrated contamination of supplements with prohibited substances, including anabolic agents and stimulants, even when not listed on labels (Geyer et al., 2004).

Risk reduction strategies include use of third-party tested products, avoidance of multi-ingredient or “proprietary blend” supplements, and preference for single-ingredient formulations. Risk can be reduced but never eliminated.

Step 6: Trial Use and Performance Evaluation

Any supplement under consideration must be trialled during training or low-priority competition. Athletes should assess performance outcomes, side effects, and consistency of response. If benefits are inconsistent or adverse effects occur, the supplement should be discontinued.

Supplements with Evidence of Performance Benefit

The IOC consensus identifies a small group of supplements with sufficient evidence to warrant consideration in specific contexts.

Creatine Monohydrate

Creatine is the most extensively studied ergogenic aid. Supplementation increases intramuscular phosphocreatine stores, enhancing high-intensity exercise capacity and repeated sprint performance (Kreider et al., 2017). It has a strong safety profile at evidence-based doses.

Optimal applications: strength and power athletes, team sports with repeated high-intensity efforts, short-duration explosive events.

Caffeine

Caffeine enhances performance primarily through central nervous system stimulation, reducing perceived exertion and improving alertness, endurance capacity, and select strength outputs (Spriet, 2014). Individual responses vary considerably—trial use is essential (Grgic et al., 2018).

Optimal applications: endurance events, intermittent team sports, activities requiring sustained concentration.

Beta-Alanine

Beta-alanine supplementation increases muscle carnosine content, improving intracellular buffering during high-intensity exercise lasting 1–4 minutes (Hobson et al., 2012). Benefits require chronic loading (4–6 weeks) and are highly context-specific.

Optimal applications: combat sports, middle-distance events, repeated high-intensity efforts.

Dietary Nitrate (Beetroot Juice)

Dietary nitrate enhances nitric oxide availability, reducing oxygen cost during submaximal exercise and improving efficiency (Bailey et al., 2009). Benefits appear more pronounced in recreational athletes than elite populations—individual testing is critical.

Optimal applications: endurance and intermittent sports with high aerobic demand.

Supplements for Correcting Nutrient Deficiencies

Supplementation for nutrient deficiencies follows a different decision pathway. A suspected deficiency must be confirmed through dietary assessment and, where appropriate, biochemical testing. Dietary modification should always be considered before supplementation.

Common deficiencies in elite athletes may include iron, vitamin D, calcium, and certain B vitamins, particularly in athletes with restricted energy intake or high training loads (Papadopoulou et al., 2024). Supplement use in this context is therapeutic, not ergogenic, and should be monitored by qualified professionals.

Anti-Doping Risk and Strict Liability

One of the most significant hazards associated with supplement use is inadvertent doping. Contaminated supplements have been repeatedly implicated in anti-doping violations, even when taken in good faith (Geyer et al., 2004).

Athletes must understand that “natural” does not mean safe or legal, label accuracy is not guaranteed, and quality assurance reduces but does not eliminate risk. Under the World Anti-Doping Code, intent is irrelevant. This reality must be central to every supplement decision (WADA, 2021).

Practical Implementation for Elite Athletes

- Supplements should complement—not replace—high-quality nutrition

- Trial all supplements well before major competition

- Use single-ingredient products whenever possible

- Monitor performance and health outcomes objectively

- Reassess the need for continued use regularly

Conclusion

Dietary supplements occupy a narrow but important role in elite sport. While a small number demonstrate credible performance benefits, most products offer little value and carry unnecessary risk. The IOC decision framework provides a clear, evidence-based pathway through this complex landscape.

The most effective supplement strategy is not aggressive experimentation, but disciplined decision-making grounded in science, safety, and sport-specific relevance.

Final principle: Treat supplements as precision tools—used sparingly, evaluated rigorously, and discontinued when benefits are uncertain. In elite sport, protecting health and eligibility is inseparable from optimizing performance.

References

Bailey, S. J., Winyard, P., Vanhatalo, A., et al. (2009). Dietary nitrate supplementation reduces the O₂ cost of low-intensity exercise and enhances tolerance to high-intensity exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 107(4), 1144–1155.

Burke, L. M. (2017). Practical issues in evidence-based use of performance supplements. Sports Medicine, 47(Suppl 1), 79–100.

Geyer, H., Parr, M. K., Koehler, K., et al. (2004). Nutritional supplements cross-contaminated and faked with doping substances. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 25(7), 545–552.

Grgic, J., Trexler, E. T., Lazinica, B., & Pedisic, Z. (2018). Effects of caffeine intake on muscle strength and power. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 15, 11.

Hobson, R. M., Saunders, B., Ball, G., Harris, R. C., & Sale, C. (2012). Effects of beta-alanine supplementation on exercise performance. Amino Acids, 43(1), 25–37.

Kreider, R. B., Kalman, D. S., Antonio, J., et al. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: Safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14, 18.

Maughan, R. J., Burke, L. M., Dvorak, J., et al. (2018). IOC consensus statement: Dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(7), 439–455.

Papadopoulou, S. K., Spanoudaki, M., Stogiannos, N., et al. (2024). Athletes’ nutritional demands. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1335303.

Spriet, L. L. (2014). Exercise and sport performance with low doses of caffeine. Sports Medicine, 44(Suppl 2), 175–184.

World Anti-Doping Agency. (2021). World Anti-Doping Code.